CO2 uptake in photosynthesis is the step where plants take in carbon dioxide from the air to make food. Plants use microscopic pores on their leaves known as stomata to bring in CO2. Sunlight provides the energy for the plant to transform CO2 and water into sugar and oxygen, which feed their growth and counterbalance CO2 in the air. Many indoor farms and greenhouses monitor CO2 levels to support more rapid and robust crop growth. Some growers increase the CO2 concentration to enhance photosynthesis, hoping for increased yields. In this blog, we’ll explore how CO2 uptake works, what facilitates or inhibits it, and how indoor cultivators can optimize it for thriving plants and larger yields.

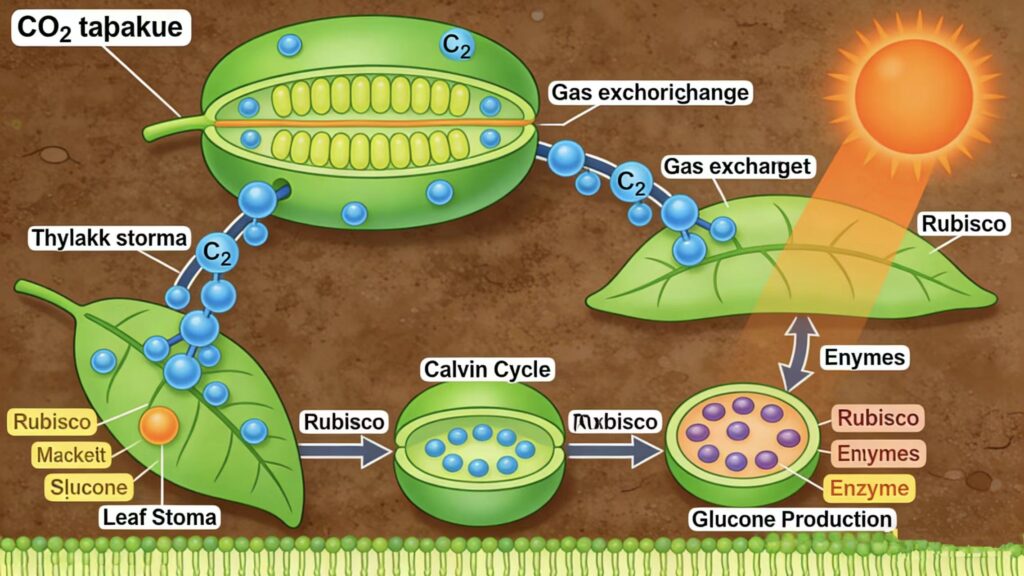

Plants suck CO2 out of the atmosphere through minute pores, stomata, located predominantly on the under leaf surface. This CO2 travels within the plant to locations known as chloroplasts, where it is transformed during photosynthesis into simple sugars such as glucose. The entire process is influenced by factors such as ambient light intensity, air temperature, and plant water availability. CO2 uptake is not exclusively focused on plant growth; it maintains plant health, facilitates root formation, and regulates hormone secretion. In closed greenhouses, CO2 can fluctuate wildly and dips during the day when plants are active and rises at night.

Stomata are like gates, allowing gases to pass in and out. They absorb CO2 but lose water. When it’s hot or dry outside, stomata will close to conserve water. Doing so greatly inhibits photosynthesis. Plants need carbon dioxide, but they don’t want to dry out. Certain plants have an abundance of stomata, whereas others have a limited amount. The distribution of stomata impacts their ability to absorb CO2 and retain water. Leaf type, age, and even where the plant grows all influence stomatal density.

Rubisco is a workhorse enzyme of photosynthesis. It captures CO2 and facilitates its conversion into sugars. Rubisco can seize oxygen accidentally, which causes photorespiration, a less productive pathway. The result is that Rubisco isn’t very fast or selective, something that can limit plant growth. Scientists are tinkering with Rubisco genes for a better carbon fixation process, hoping to produce smartly growing crops.

About the CO2 uptake process. It consumes ATP and NADPH energy, both produced in the light-capturing steps of photosynthesis. The cycle is critical to maintaining the plant’s energy balance and converting sunlight into nourishment. It loops and requires regular CO2 and adequate light to continue.

Plants employ various mechanisms to absorb CO2. C3 plants do it easily, but they lose more water. C4 and CAM plants have modifications that help them conserve water and function better in arid or hot environments. These routes influence crop growth in various climates, which is important to farmers everywhere.

CO2 uptake drops if the plants get too hot, too cold, or don’t get enough light. Bad weather, such as droughts or heat waves, can curb photosynthesis and growth. If there’s too much CO2, plants can’t always use it all, which is called CO2 saturation. Understanding these thresholds helps growers maintain plant health and yields.

Increased carbon dioxide in the air can alter plant growth and energy usage. If the air contains more CO2, most plants can leverage this to accelerate photosynthesis. C3 plants such as wheat and rice tend to experience the most significant increases, with yields increasing by 40 to 100 percent at CO2 concentrations of 800 to 1,000 ppm, given sufficient water and nutrients. C4 plants like maize and sugarcane grow more, but their yields increase by 10 percent to 25 percent in these same conditions. This photosynthesis surge occurs because plants use CO2 to produce sugars, which they then store and use for growth. Even so, over time this effect may slow as plants acclimate to higher CO2, a process called acclimation. For instance, white clover at 600 ppm CO2 maintained a 37 percent boost in photosynthesis after eight years, but the advantage diminished.

Elevated CO2 can result in larger, more rapid plant growth. It’s not necessarily a straightforward victory. If plants grow more quickly, they may not absorb minerals from the soil as efficiently. This can alter the protein or starch content of foods such as wheat or rice. Research indicates that wheat exposed to higher CO2 levels will produce grain with altered protein content and flour texture. Soybean plants display shifts in sugar and nutrient use that impact seed quality. We found that glucose, a simple sugar, plays a bigger role in how plants grow and respond to more CO2 in the air. Roots aren’t exempt either. Tomato roots, for instance, emit more ethylene, a plant hormone, when CO2 rises that can assist roots to disperse or morph.

The real impact of elevated CO2 is conditional on other factors as well. If it’s warmer or nitrogen is more scarce, the plants may not grow as much despite the increased CO2. For rice, shoot growth and photosynthesis with added CO2 may be either enhanced or limited depending on temperature and nitrogen availability. These shifts are significant because they affect food quality, crop yield, and the future of food security globally.

CO2 uptake influences many other plant processes well beyond leaf photosynthesis. Green tissues such as stems and certain fruits take up CO2 and help with carbon assimilation, but at different rates. Fruits, for instance, have just 1 to 10 percent of the leaf density, with apples being even lower—roughly 30 times less. In wheat, non-leaf organs may account for 27 to 62 percent of the total green area per culm, particularly under water deficit conditions. These tissues absorb atmospheric CO2 and recycle CO2 produced by their own respiration.

Plants convert CO2 to sugars in photosynthesis. Sugars aren’t just energy storage. They function as messengers, informing the plant when to develop or pause and how to respond to its environment.

When CO2 increases, plants make more sugar, which tips the balance of signals. This may alter growth, accelerate flowering, or enable plants to more effectively cope with stresses such as drought or insects. Sugar signaling helps plants determine how best to allocate stored energy during stressful periods. With more CO2, these pathways may shift, changing how plants respond to their surroundings.

CO2 doesn’t alter what occurs above ground. Elevated CO2 can enhance root growth in terms of thickening or elongation. This change in root shape alters how efficiently plants absorb water and nutrients.

A plant’s root-to-shoot ratio can change when CO2 increases. At times, more roots develop than buds, rendering these plants superior at mining the ground for its nutrients. This is vital for living through drought or nutrient deficits. Deep, intricate roots enable plants to withstand challenging environments, a necessity as climates change globally.

Plants aren’t just passive chandeliers waiting for nourishment — they prey on it. When CO2 rises, plants could alter the dynamics of root growth and the chemistry they exude into the soil. These chemicals, called exudates, can lure beneficial microbes.

Elevated CO2 frequently leads to increased root exudation, which in turn can nourish soil microbes. These microbes degrade nutrients, facilitating their uptake by plants. If soil lacks certain nutrients, plants need to modify their foraging strategies. Understanding how plants and microbes respond in concert to shifting CO2 is crucial for sustainable agriculture globally.

CO2 absorption in photosynthesis links directly to the way plants utilize and transport nutrients. As plants suck in CO2, they require an adequate supply of nutrients, principally nitrogen, to convert that gas into sugars and eventually components such as leaves or stems. This handy link between carbon and nitrogen is important because nitrogen constitutes amino acids, nucleic acids, and chlorophyll. If there isn’t enough nitrogen, even with abundant CO2, plants can’t grow well or remain healthy.

High CO2 may alter the way plants capture and utilize nitrogen. One study found that when CO2 increases, plants might absorb less nitrogen, modifying the carbon nitrogen ratio. This shift can reduce nutrient densities in plant tissues, impacting not only development but the nutritional quality of produce. The signaling pathways for glucose and nitrate within the plant can adjust how roots take up and utilize nitrogen from the soil. The sum of these small variations can become significant, particularly when plants are under stress such as drought or heat. If nutrients aren’t in proportion, plants may invest more in making sugars at the expense of proteins or other essential compounds.

Micronutrients play a role, like iron, zinc, and magnesium. They assist with enzyme function and allow plants to efficiently utilize CO2 during photosynthesis. For instance, magnesium occupies the central position of the chlorophyll molecule, enabling plants to absorb light and utilize CO2. If any of these micronutrients run short, plants can’t capitalize on elevated CO2. Research finds that even mild deficiencies of these nutrients can reduce photosynthetic rates and constrain how much CO2 plants consume.

Balanced nutrient management is key for plant growth and good CO2 uptake.

Knowing this interplay aids growers in optimizing fertilizer application and crop selection. It informs irrigation, crop selection, and stress management decisions in every climate zone. Plants require more than simple doses of CO2; they require the right nutrients in the right mix at the right time.

The quality dilemma in plant science is just plain tough. As we all know when discussing CO2 uptake in photosynthesis, there’s always the struggle to increase yield while maintaining crop quality. It’s not as easy as ‘more is better’. Increased CO2 may promote accelerated growth, but it can change the internal composition of food—such as nutrients, starch, and taste.

Elevated CO2 frequently results in larger plants and more biomass. At first glance, this appears excellent. A number of studies indicate that as we make crops grow more rapidly, the part we eat—grain, fruit or leaves—may not be as nutritionally dense. For instance, wheat or rice cultivated in elevated CO2 emissions may contain an increased number of carbohydrates but exhibit a reduction in protein and minerals such as iron or zinc. Tomatoes or lettuce may appear lush but be less vitamin or nitrogen-rich. This yield versus quality trade-off stings the most when resources such as nutrients or water are low or when quality takes a back seat to cost and speed, like on mega-farms.

Nutrient density is a big food security issue. If they grow faster but lose important nutrients, the quantity gains may not serve people’s health. Differences in starch accumulation or changes in nitrogen usage by plants are much more relevant in this regard. Research indicates alterations in root systems and sugar metabolism under elevated CO2. Although these alterations can assist plants in making better use of water, they can translate to diminished flavor or shorter shelf life.

Consumer perspectives count as well. A lot of people seek flavor, nutritional value, and freshness—not just size or color. Shoppers in markets across the planet determine quality by how a tomato smells or a leaf feels, not by how big it is. Certain consumers will pay a premium for superior taste or nutrition, while others will be more concerned about price or appearance. Even the meaning of “quality” can vary from culture to culture or individual to individual.

Tackling the quality dilemma requires equilibrium. Growers, scientists, and buyers all influence what makes it to the plate. Decisions regarding CO2, fertilizer, and water need to take into account what is gained and what may be sacrificed. Serving everyone requires defined aims, inclusive thinking, and candid discussion about compromises.

Controlling CO2 is the secret to optimizing photosynthesis in agriculture, particularly indoors or in greenhouses. First, plants absorb CO2 via stomata during the day. CO2 levels are often higher at night because of the breathing of plants and of microbes in the soil. Managing CO2 keeps crops strong.

Plant CO2 uptake is measured with gas exchange systems. They measure CO2 intake and output in a plant leaf. In research and big farms, infrared gas analyzers are employed for on-the-fly results. By measuring CO2 correctly, growers can know when plants require more or less. It identifies optimal times to dose CO2, typically an hour or two after sunrise and ceasing a couple of hours before sunset.

Taking CO2 measurements outside presents its own issues. Wind, sun, and fluctuating temperatures cause readings to bounce. That’s why indoor farms leverage sealed rooms and constant airflow to maintain stable numbers. New tech has assisted significantly. Portable meters, sensors that transmit to your phone, and improved software simplify and increase the precision of monitoring CO2.

Supplementing CO2 in greenhouses or indoor farms accelerates plant growth and produces higher yields. When CO2 reaches 1300 ppm, plants can operate photosynthesis at full throttle. For a 200-square-foot room, 5 ounces of ethyl alcohol per day can maintain CO2 at this level. Dry ice is one method, as it is simply frozen CO2. A few farms burn fuel to make CO2, but for every pound of fuel burned, you get 3 pounds of CO2.

CO2 must be handled correctly. Carbon monoxide is a risk if things go awry and should never exceed 50 ppm, or it can damage plants and humans. CO2’s price is real, but that leap in yield can pay for itself with most crops. Automated CO2 controllers are a great way to save time and keep levels consistent.

CO2 is the primary fuel that plants consume. Healthy CO2 uptake in photosynthesis helps plants produce more food and grow more rapidly. Too much or too little CO2 uptake in photosynthesis affects growth. Roots, air, and food in the soil connect with CO2 uptake in photosynthesis. Maintaining the appropriate CO2 blend enables cultivators to achieve consistent harvests with enhanced flavors and appearance. A tomato farm in the Netherlands experienced larger fruit and richer color with precise CO2 management. CO2 is a best friend with smart care—good air, light, and water. To maximize every crop, monitor your CO2 frequently. Want to witness how superior CO2 uptake for photosynthesis can work for your plants? Take a test. Grow smarter, not harder.

CO2 uptake in photosynthesis is when plants take carbon dioxide out of the air and convert it to energy-rich sugars using the sun.

High co2 typically increases growth by increasing photosynthesis. The advantages can be contingent on other factors such as nutrients and light.

Yup, leaves are where most of the CO2 uptake happens. They have minuscule pores called stomata that control the amount of CO2 that gets into the plant.

Not necessarily. Although more CO2 can accelerate growth, it might not enhance crop quality or nutrition if other resources are scarce.

CO2 uptake goes best when nutrients are in balance. If nutrients are scarce, then plants cannot fully utilize the additional CO2, restricting growth and yield.

Yes, you can get controlled CO2 enrichment in indoor grows to increase yields, provided you have sufficient light, water, and nutrients.

Track and tweak CO2 levels depending on plant species and growth phase. For precise control, particularly indoors, use ventilation and CO2 supplementation tools.

Contact us to find the best place to buy your Yakeclimate solution today!

Our experts have proven solutions to keep your humidity levels in check while keeping your energy costs low.